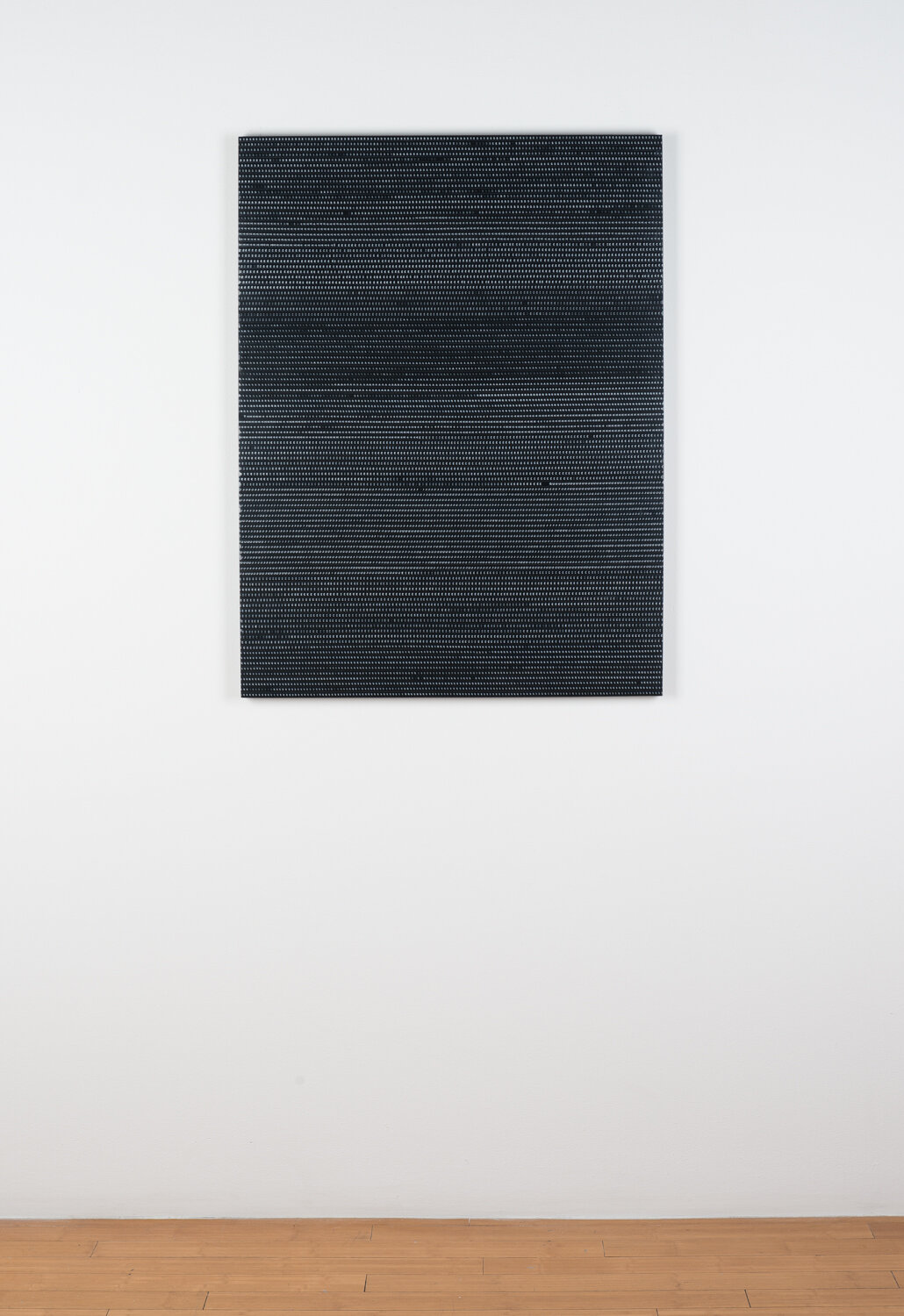

SMEAR THE QUEER

2020

DYMO® label tape on wood panel

40 x 30 x 1.5 inches

“Smeared Labels”

“To make things queer is certainly to disturb the order of things”

—Sarah Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, 2006

In elementary school, we played a game called “Smear the Queer.” In my experience, this game was only ever played by boys. To play the game, one person had the ball—the queer— and everyone would try to tackle him. Once tackled, he would throw the ball in the air and whoever caught it would become the queer, and the game would continue. No one won; it was a zero-sum game. The game only ended when recess was over or someone got hurt.

I never learned to throw a ball, so I avoided playing the game. But my fear of throwing a ball exceeded my fear of being viewed as different. So, at my small fundamentalist Christian school in rural Michigan, I played the game. This game, like so many others, was fundamentally about language and identity, being “it” or “not it,” being same or other.

I grew up during the AIDS crisis when queer bodies were feared, stigmatized, and vilified. This fear of the queer body shaped who I am today. It shaped my own body, its movements and orientations. At that point in my life, I didn’t identify with the word “queer,” but I knew I was different, that I was attracted to bodies that looked similar to mine. I was jealous of the pretext of the game, that someone could so easily become, and un-become queer. Being raised in an evangelical home resulted in years of “reparative therapy.” I prayed so many times that I could become un-queer. I wished life could be as simple as the game: just let go of the ball.

Yet this game also offered a socially acceptable way for me to touch the bodies that I was attracted to. As long as I was tackling or hitting another player, this touch was acceptable. This contact became the only safe way to get the touch I desperately wanted. I mimicked the aggressiveness of other boys but made it my own; playing sports was my queer performance.

Many years later, I was mentored by conceptual artist, Barbara Kruger in graduate school. She taught me the power of a phrase, a pronoun, or a word. When I thought of myself as an experimental writer, Kruger helped me see that my true interest was in language at a more fundamental and at a conceptual level. Her economical but potent use of words helped shape the way I approach art and language.

I think of her artwork, untitled (You Construct Intricate Rituals) (1981) where she overlays "You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men" in her signature Futura Bold Oblique typeface across a found photograph of seven smiling suited men engaged in some type of physical struggle. Her pithy text transforms the image into a critique of socially appropriate masculine contact. In my own life, I traded those suits for a football uniform, and I perfected these rituals, channeling my repression/aggression while seeking the touch and social acceptance I craved.

We learn through games: they are structural and instructional as they encode and reflect our societal norms and values. They provide a supposedly safe space to interact with and enact identities, allowing us to rehearse the roles we are expected to perform. Games teach us how the world works and, as adults, we keep playing them.

These formative experiences with words and games are foundational for my practice as a conceptual artist working with language. I explore the complex interplay between societal labels, cultural norms, and the rituals we construct to navigate them. My work "SMEAR THE QUEER" delves into the memories of this formative childhood game and the complex dynamics it embodied.

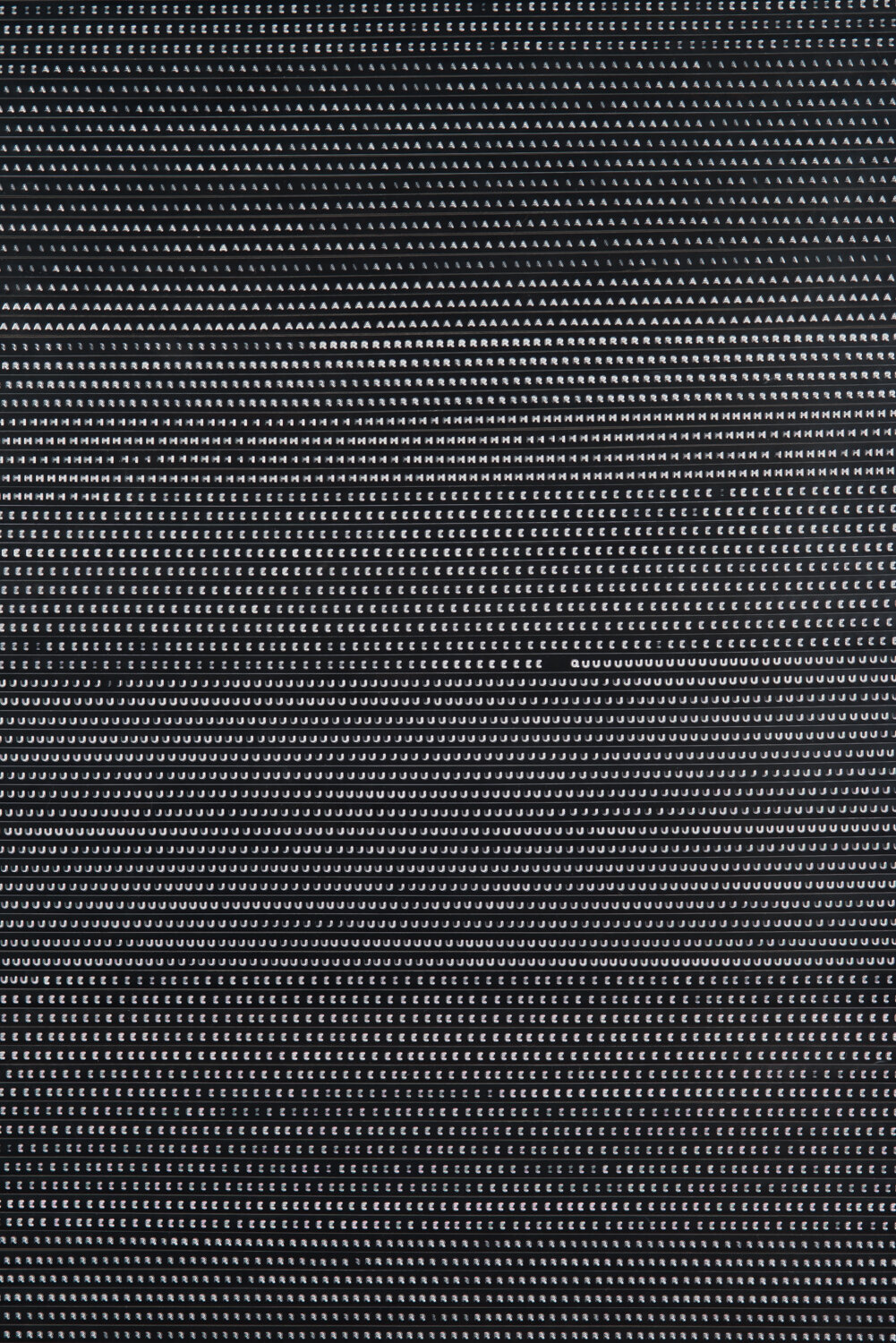

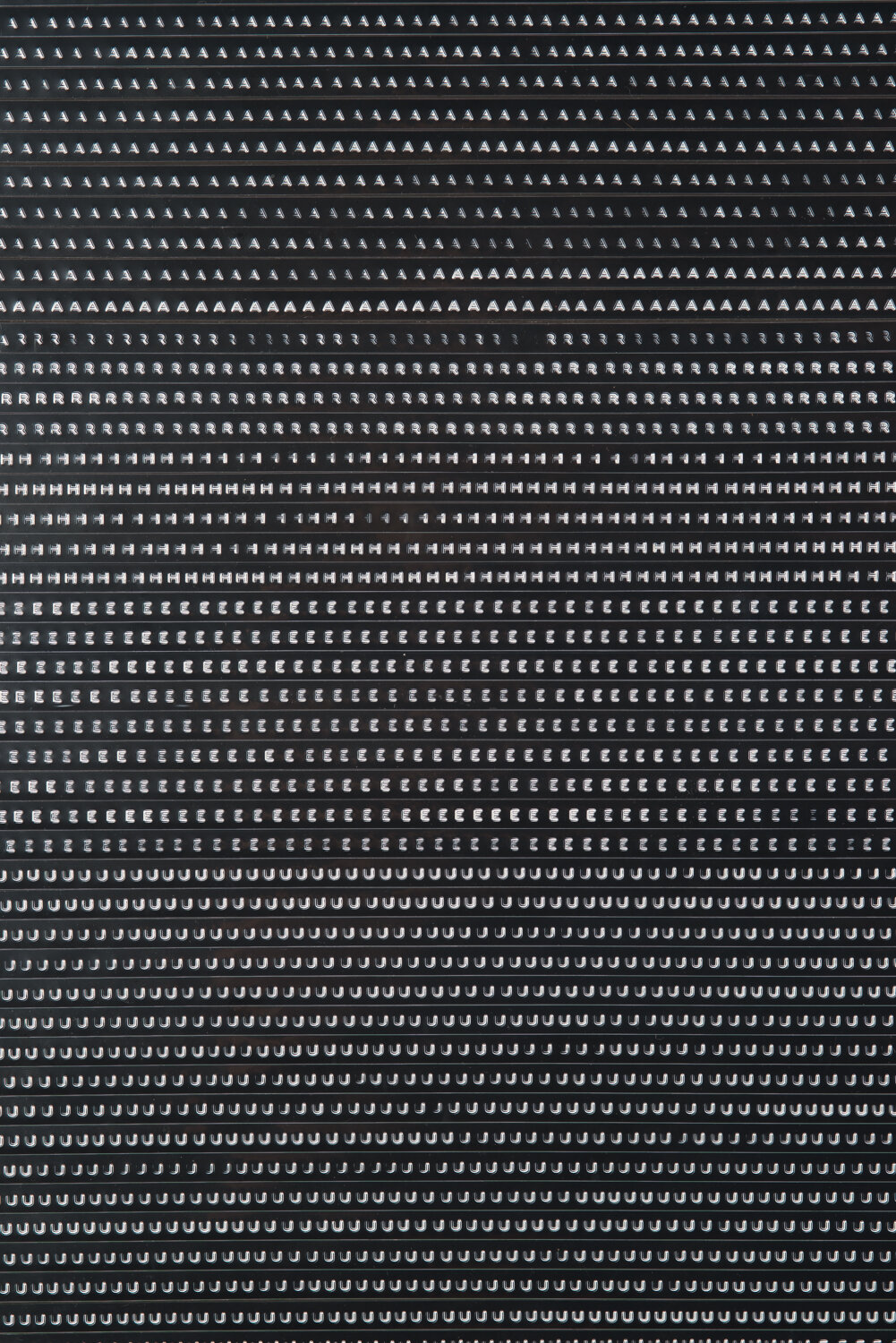

The piece utilizes a DYMO™ label maker—a device I fondly remember from childhood—to phonetically stretch and distort the phrase. I apply my own rules to this distortion: any letter that can be phonetically elongated, such as "S" and "M," I repeat extensively ("SSSSSS" and "MMMMM"), while letters that cannot be elongated, like "Q," appear only once. This approach asks the viewer to consider the space between written language and the performance of reading—the space between knowing and being. Each letter is unique, forming a plasticky surface that displaces and distorts the loaded phrase. The shiny tactility of the embossed letters begs to be touched, denied by the cultural prohibition of not “touching the artwork.”

Where Kruger's work directly confronts power dynamics through stark contrasts and declarative statements, my work creates a more ambiguous space. I develop a queer orthography based on non-normative speech practices like lisping. As scholar Sara Ahmed writes, "To make things queer is certainly to disturb the order of things," and this distortion deliberately frustrates and complicates the act of reading. It plays the game of language but bends the rules. It resists the immediacy of language, providing a space of deferment—perhaps similar to that childhood game allowing me to perform but avoid the literalness of my identity.

I'm not trying to "reclaim" this phrase—it's not mine to reclaim. Rather, I aim to disrupt the ease and immediacy of reading, creating a space where viewers must confront the power language holds over our bodies and identities. Through this work, I explore the simultaneously reductive and necessary nature of labels, the intricate rituals we construct to navigate identity, and the charged spaces between language, performance, and the perpetuation of societal norms. “SMEAR THE QUEER” serves as a meditation on the complexities of queer experiences, the formative games we play, and art's potential to unsettle and reshape our personal and collective narratives.

—Joel Swanson